| Subject | Orte | Personen |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

To understand the phenomenon of emigration from the Valais, the causes must be looked for on both ends of this process: in the land of departure and in the land of destination. Ignoring this necessity would expose us to the fallacy of ethnocentrism; that is, of considering the question solely from one's subjective point of view and according to the values and ideologies of the society to which one belongs. For example, the Valais of today has become a place of immigration, and it is easy to lose sight of the fact that the immigrants who now come to the canton are also emigrants who left their families and friends, as well as difficult situations, behind them, often in the context of war.

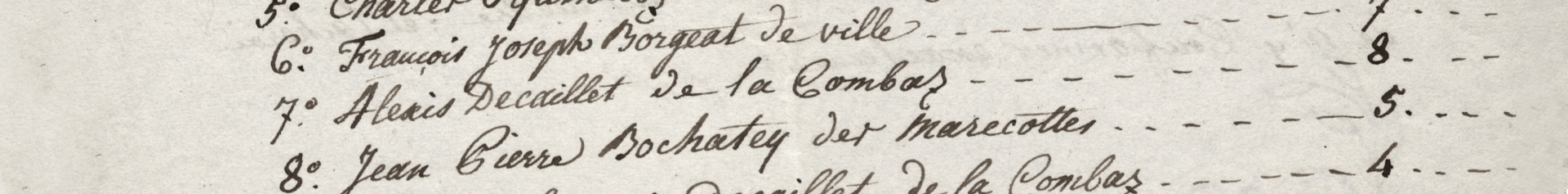

Speaking of the military emigration within the framework of the Valais foreign service until the 19th century, it goes without saying that war constituted its direct and official objective. However, when it comes to the emigration of the population, the relationship to war may not have been at the heart of the emigrants' plans and motivation, yet it was ubiquitous in all the territories that Valaisans were called to populate in large numbers during the 19th century. It was often in the context of wars, especially invasions, that the emigration of the Valais population unfolded, as was the case in other cantons or neighbouring countries. In the hopes of finding a better future, the inhabitants of the Valais left in large numbers a country that was not at war in order to participate in the internal war efforts of the countries that "invited" them. This participation, which includes taking up arms, had the principal aim of colonizing territories from which native populations had been or were being expulsed.

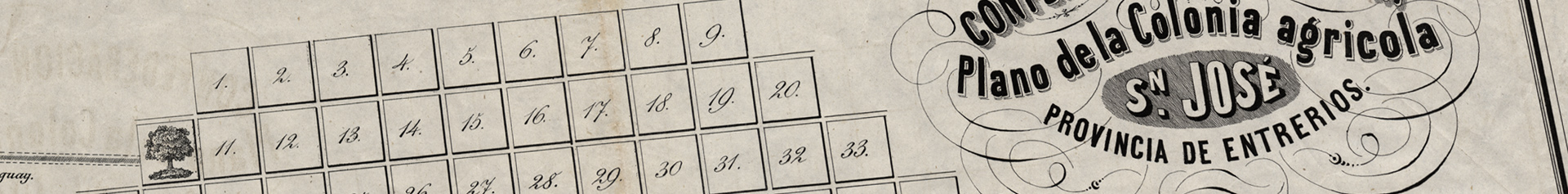

In the case of population emigration, it was not a matter of providing a fighting force either, but a labour force for the economy of the countries of immigration. Amongst these, we must distinguish between those which, when the settlers from the Valais arrived, were still under the colonial administration of the home country—like Brazil and Argentina—and those that were under the control of states that had recently gained their independence, like the United States, and in particular Chile and Argentina. In the latter country the official motto concerning immigration policy was: "To govern is to populate". However, the "populating" was not to be done in a random manner, since at stake for the authorities was the imposition of white supremacy. The Europeans settlers—preferably from northern Europe—were deemed more naturally capable of accomplishing the task of "civilization" and the project of economic development of local elites, who were themselves descendants of the original Spanish colonists. The achievement of these goals was made possible by the wars waged against the Amerindian populations; these were so violent in some cases that they took on the aspect of an extermination. In Chile, this war of territorial conquest was treated as a process of "pacification". In Brazil, being Catholic was one of the conditions that had to be met for immigration. In every case, the settlement policy appeared as the continuation of war by other means.

Therefore it is reductionist to oppose—as has often been done—the Valais as a land of emigration with overseas countries destined for immigration, for the latter were able to become lands of immigration only at the price of the forced emigration, within these new nations, of an entire sector of the population. The fact is that the settlers from the Valais, whatever else fate may have had in store for them, and sometimes unbeknownst to them, were called to participate in these campaigns of territorial conquest. Still today some descendants of the native population are demanding justice and compensation. In giving an account of these events, therefore, one must be careful not to repeat in words the violence of actions, and not to confuse "New World" with new States, "desert" with the lands of the Mapuche, or "pacification" with war. Adopting this terminology amounts to rewriting the history of emigration according to the unilateral mode of a colonial epic.

To consider this migratory episode solely from the angle of emigration results is blinding us to the possible points of comparison between the situation of the lands of immigration and that of the Valais. Leaving the question of territorial size aside, countries like Argentina and Chile during the second half of the 19th century shared with the Valais the fact of being under the control of states that were still in the process of formation and that developed agricultural programmes consisting in making infertile land fertile; this in order to achieve exportation objectives within the context of an emerging capitalist economy. There was widespread poverty in each of these countries, although according to the logic of colonial relations, the Valais had the privilege of being situated on the "right side" of the world. A one-sided view of things also prevented justice from being done to many Valais emigrants who were instrumentalized on both ends of their migratory odyssey. They were given the promise of arable land and gains as lucrative as they was remote, only to find themselves in the front ranks of a war that refused to call itself by its name, then to join the ranks of a nascent urban or peri-urban proletariat, on the side of Argentinian workers. The historical documents left by these people for posterity are rare, if not non-existent. Faced with these unwritten pages, there is a tendency to concentrate on "success stories" that are in keeping with the contemporary values of our Western societies, and therefore open to being reappropriated in the name of present-day memorial and identitary agendas.

As had been the case with the foreign service, the population emigration, which changed the lives of thousands of people in the Valais, also appears as having been an instrument in the hands of various powers. These two types of emigration were not just in a chronological relationship—the one taking the relay of the other—but also in a mutually functional relationship. To say that there were as many causes for emigration as there were emigrants is a truism that makes it impossible to grasp the economic and social forces in which the migrants were caught. The military instrument of territorial expansion, the instrument of racial policies, the instrument of a policy of riddance, the population emigration was also an instrument of commerce.

Bibliography

Patricia PURTSCHERT & Harald FISCHER-TINÉ (ed.), Colonial Switzerland. Rethinking Colonialism from the Margins. Ed. Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Joachin MANZI, "L’accueil de l’immigrant dans l’invention de l’Argentine moderne," in V. DESHOULIÈRES and D. PERROT (ed.), Le don d'hospitalité: de l'échange à l'oblation, Presses Universitaires Blaise Pascal, 2001, pp. 113-136.