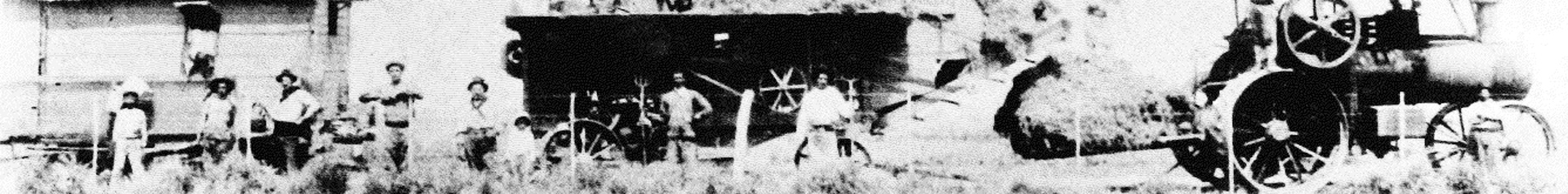

Starting in the 19th century, the wave of emigration to the Americas also reached Switzerland, and the Valais in particular. The new countries overseas were looking for European labour in order to launch their export economies, especially in the agricultural sector.

Some emigrants left for the Americas already between 1819 and 1851. Afterwards, during a period of several years, a number of families from the Valais also left for Africa, mainly to got to Algeria. The year 1857 marked the beginning of a strong wave of emigration toward South America, especially to Argentina.

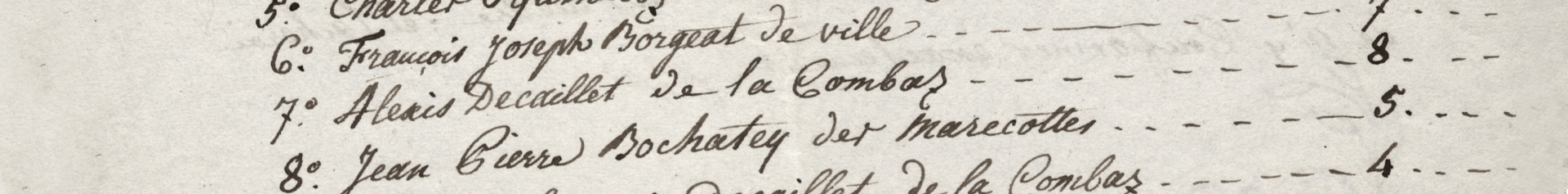

During the first half of the 19th century, industry in the Valais was still in its infancy; those who did not find any work in the Valais tried their luck elsewhere and filled the ranks of the emigrants. In the face of this growing phenomenon, Valaisan authorities reacted by setting limits on the number of departures. To that end they adopted legislation to regulate the agencies for emigration and to prevent the departure of persons who were not able to provide for their own needs. The State Council sought to "protect the citizens of the Canton who intend to emigrate from reckless decisions and to guarantee the fulfilment of the promises given to them by the emigration agencies". Concretely, "the emigration of persons who, lacking the requisite intelligence or the resources to meet their needs, and who consequently are in danger of dying of deprivation or being sent back to their towns, is absolutely prohibited".

This law made the Valais a very protectionist canton in the matter: after the fiasco of the Pache convoy in Marseilles, the government even considered prohibiting emigration.

Since the middle of the 19th century millions of Europeans and hundreds of thousands of Swiss citizens emigrated, going abroad in search of new living conditions. This trend accelerated in the Valais starting in 1857, and peaked between 1868 and 1875; after a brief lag, emigration picked again between 1882 and 1892. Before 1880, the largest contingents of emigrants came from the districts of Conches, Rarogne, Brig, Viège, Monthey and Hérens; after 1880, emigration increased in the districts of Conches, Sion, Martigny and Hérens, while it decreased in the districts of Rarogne, Monthey and Entremont. Generally speaking, there were more departures from mountain areas than from the plains. The majority of the emigrants left for the United States and Argentina.

The construction of a railway system in the Valais facilitated exchanges, and therefore a first turning point in the economy of the Valais: after a period of stagnation until around 1895, imports increased considerably starting in 1900, and exports starting in 1905. The industrialization of the country brought with it an improvement in the standard of living for the Valaisan population. With the First World War, overseas emigration came to an end.

When we think about emigration from the Valais, we often imagine thousands of people leaving to establish themselves overseas during the 19th and at the beginning of the 20th century. The attention paid to this population emigration can be explained by the numbers, as well as by the genealogical and identitary issues involved. However, this should not make us lose sight of the fact that this was one historical form of emigration among others and that, long before the departures for the Americas and North Africa, men and women from the Valais left their homeland either temporarily or permanently. Thus the population emigration took the relay of a military type of emigration, which for centuries saw many Valaisan men leave in the service of foreign powers, in order to earn a living and sometimes to find glory—or to die.

Military emigration: from mercenaries to the foreign service

It is difficult to date the beginnings of military employment abroad, but the presence of mercenaries from the Valais in the service of the kings of France is attested as early as the 13th century, and it already represented a sizeable number in the late 15th century, during the wars between Burgundy and Italy. More...

Population Emigration

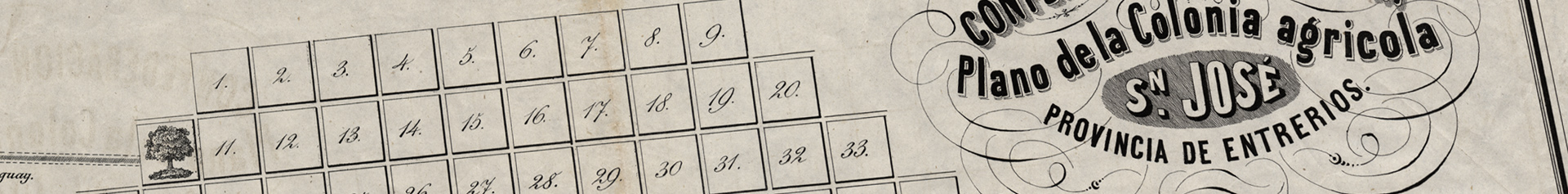

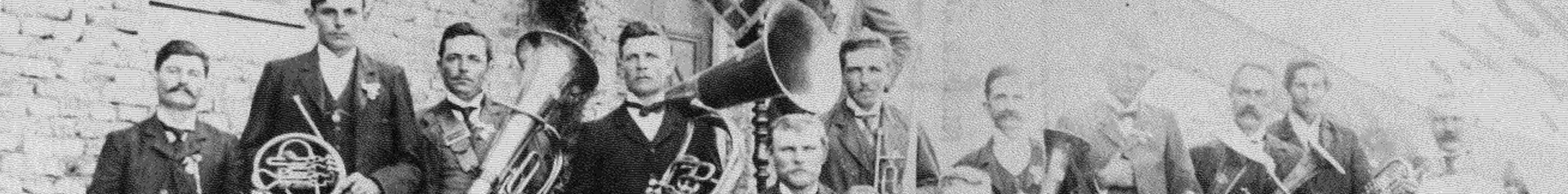

Throughout the 19th century, at the same time that foreign service from the Valais was winding down, a new form of emigration came into being that affected a large number of inhabitants of the Valais and that can be called population emigration. Indeed, it no longer involved temporary sojourns in foreign countries in view of a specific mission, but a form of emigration to countries overseas that was often considered to be definitive, and in which the emigrants were called to establish themselves as landowners. Thousands of persons and families left the Valais in the hopes of finding a better life, especially in Argentina (1855), but also in Brazil (1819), Algeria (1851), and Chile (1883). There too, however, they experienced many disillusionments, both during their travels and upon their arrival, such that many returned to the Valais. More...

Religious emigration

From "sacred imperialism" to the "ambassadors of the Valais" More...